Fushimi Inari Shrine in Kyoto is one of the most famous Inari shrines in Japan—but why is it so renowned?

As the head shrine of all Inari shrines across Japan, Fushimi Inari is known for its blessings in business prosperity and the worship of fox deities. However, it also holds a deep-rooted history of faith, with people praying here for bountiful harvests, safety, and other blessings for centuries.

The expansive shrine grounds are home to various smaller shrines and mounds, each carrying unique and mysterious tales. Learning about these stories can make your visit even more meaningful and give you a deeper experience.

Be sure to add Fushimi Inari to your list when exploring Kyoto!

What is Fushimi Inari taisha Shrine?

Located in Kyoto’s Fushimi Ward, Fushimi Inari is the head shrine of approximately 30,000 Inari shrines throughout Japan. Its formal name is Fushimi Inari Taisha, but we’ll refer to it as Fushimi Inari here.

Founded in the Nara period, Fushimi Inari has a long history with various changes over the centuries. It’s especially popular among the public for its blessings in business prosperity and is ranked as one of Japan’s most visited shrines, especially for New Year visits—drawing over 2.5 million people during the first three days of January alone.

Fushimi Inari is also well-known for its mesmerizing Senbon Torii, or “thousand red torii gates,” which have made it a favorite spot among international visitors.

There is also a popular term, the “Three Great Inari Shrines of Japan,” which often includes Fushimi Inari, though the list isn’t fixed. Other commonly mentioned Inari shrines include Toyokawa Inari in Aichi, Yutoku Inari in Saga, and Kasama Inari in Ibaraki.

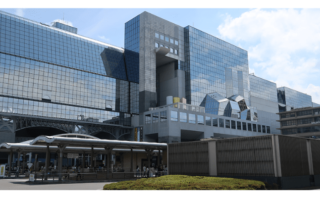

The shrine is easy to reach; it’s just a few minutes’ walk from JR Fushimi Station or Keihan Fushimi Inari Station. Near the main shrine, you’ll also find Mount Inari, a sacred area filled with more shrines and mounds that add to the mystique of Fushimi Inari.

Below, we’ll explore more about Fushimi Inari’s history and the fascinating stories associated with it. Enjoy the journey!

What’s at Fushimi Inari?

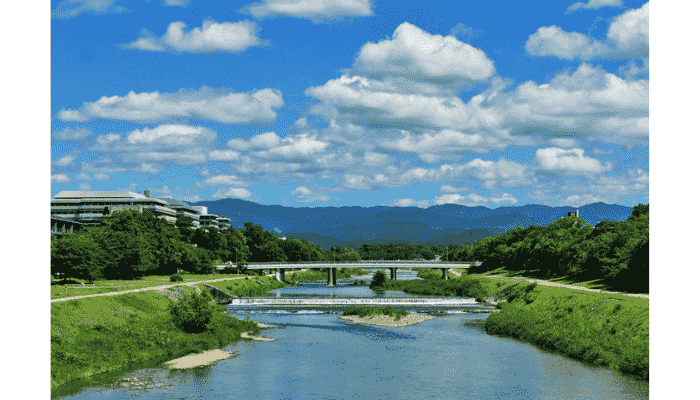

Fushimi Inari covers all of Mount Inari, located at the southern end of Kyoto’s Higashiyama mountain range. The shrine grounds are enormous—about 22 times the size of Koshien Stadium!

With so many buildings and shrines across this vast area, first-time visitors may find it hard to know where everything is and where to pay their respects.

To make things easier, let’s divide the main sites into two areas: the Mountain Base Area and the Mount Inari Area.

Most visitors focus on the Mountain Base Area, where the main shrine buildings are located. The upper Mount Inari Area offers a more challenging trek and requires additional time.

Regular Visits Center Around the Mountain Base Area (Main Shrine to Okunoin)

(1) Romon Gate

When visiting Fushimi Inari, you’ll start the approach from JR Inari Station or Keihan Fushimi Inari Station, where you’ll soon arrive at Romon Gate (the gate beyond the torii in the photo above).

This grand gate marks the entrance to the shrine grounds and was built by Toyotomi Hideyoshi. It’s also designated as an Important Cultural Property of Japan, so be sure to take a closer look at its remarkable architecture.

(2) Gehaiden (Outer Worship Hall)

Next, you’ll reach the Gehaiden, or Outer Worship Hall, also known as the Dance Hall. Events like the Setsubun festival in February are held here, including traditional bean-throwing ceremonies.

The Gehaiden is not used frequently and is less visited by worshippers, but it’s a stunning structure built around the same time as Romon Gate and is also an Important Cultural Property.

(3) Honden (Main Hall) and Naihaiden (Inner Worship Hall)

Just past the Gehaiden, you’ll find the Honden, or Main Hall, and the Naihaiden, or Inner Worship Hall.

The two halls are attached, with the Honden being closed to entry, so visitors typically pay their respects at the Naihaiden. This is the central place for worship. The current Honden was rebuilt in 1499 after it was destroyed during the Onin War. Its elegant yet bold design has earned it the status of an Important Cultural Property.

Inside the Honden are five deities, which is rare and known as an Ichiu Aiden. Originally, the shrine honored three deities, with two more added later:

- Shi-no-Okami

- Ukanomitama-no-Okami: The main deity

- Satahiko-no-Okami

- Oomiyanome-no-Okami

- Tanaka-no-Okami

(4) Okusha Hohaisho (Inner Shrine Worship Hall)

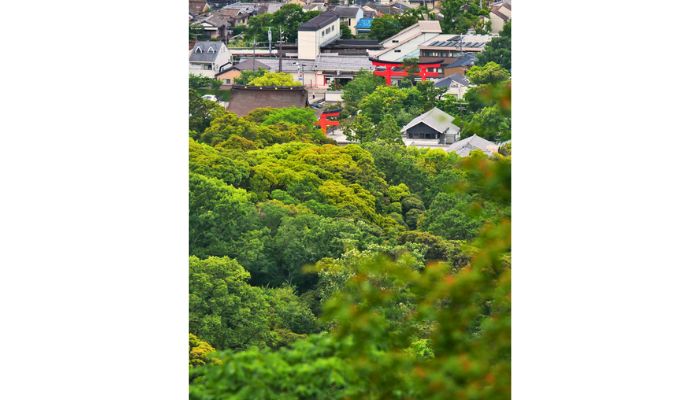

Behind the Main Hall lies the famous Senbon Torii, or “Thousand Torii Gates,” which leads to the Okusha Hohaisho, pictured above. This area, often called the Oku-no-in or “Inner Sanctuary,” sits in front of the three peaks of Mount Inari and serves as a place to pray to the mountain itself.

For those with time, visiting both the Main Hall and then continuing through the Senbon Torii to the Oku-no-in is recommended.

The round trip from JR Inari Station or Keihan Fushimi Inari Station to the Oku-no-in takes about one hour if you’re in a hurry, or around two hours if you’d like to enjoy the Senbon Torii path at a leisurely pace.

While the Oku-no-in has long existed as a sacred site, the current building dates back to the Edo period.

Exploring the Mountain hike of the Inariyama Area

Above the Oku-no-in, the path leads up into the Inariyama mountain trails, where you can visit the First, Second, and Third Peaks.

The highest point, the First Peak, is 233 meters above sea level. Here, you’ll find the Suedakisha Shrine (pictured below), a site with a long history of worship and sacred significance. There are even rumors that the fortunes, or omikuji, sold here are particularly accurate—but who knows?

The full “Oyamameguri” (Mountain Pilgrimage) trail around Inariyama takes about 1 hour and 30 minutes at a brisk pace from the Main Hall back down, but if you’d like to take it slow, plan for around 3 hours.

Throughout the mountain, you’ll find many other smaller shrines and mounds. Some of the main ones are mentioned in the following section, where we share some fascinating stories about this sacred mountain.

Getting to Fushimi Inari Taisha

Here’s how to reach Fushimi Inari Shrine:

If you’re coming from central Kyoto by train, take the JR Nara Line from Kyoto Station and get off at Inari Station. The main approach to Fushimi Inari Shrine is right in front of the station.

Alternatively, if you’re on the Keihan Main Line, get off at Fushimi Inari Station, located on the west side of JR Inari Station. From here, it’s about a 5-minute walk along the back approach to reach the Main Hall. This path is lined with many shops.

If you’re driving, it takes about 20 minutes from the Kyoto Minami IC on the Meishin Expressway or 10 minutes from the Kamitoba exit on the Hanshin Expressway.

There’s a free parking lot for regular vehicles near the Romon Gate, though it can get crowded during peak seasons. You may be directed to a lot farther away. Additionally, private parking is available in the area.

History of Fushimi Inari Taisha Shrine

(1) The Nara Period (Founding)

There are several legends about the origin of Fushimi Inari Shrine, but here’s a popular story. According to the Yamashiro no Kuni Fudoki, a historical document, Fushimi Inari was founded during the Wado era of the Nara period (circa 711). It is said that Hata no Irogu, a member of the Hata clan who lived in the Fukakusa area, shot an arrow at a rice cake, which transformed into a white bird and flew away. The bird landed in a field where rice suddenly grew, surprising everyone. This miraculous event led them to build a shrine on that very spot, marking the beginning of Fushimi Inari Shrine.

The shrine was originally written as “Inari” (伊奈利), but later became “Inari” (稲荷), referring to “rice load” in Japanese. The Hata clan, who are believed to have come from China or Korea, established themselves in the Uzumasa area of Kyoto and are also associated with Matsuo Shrine and Shimogamo Shrine.

(2) The Heian Period (Growth and Fox Legend)

During the Heian period, the Fushimi Inari area prospered, and around the 820s, Emperor Junna fell ill. An oracle revealed that the illness was due to trees cut from Fushimi Inari’s sacred forest to build Toji Temple. To appease the gods, he granted the shrine the title of “Junior Fifth Rank,” officially recognizing its status. Over time, it gained even higher ranks and became a central place of worship for good harvests and prosperity.

The connection between Fushimi Inari and foxes (kitsune) also began to take root in the Heian period. There are various theories about this link, but one popular story suggests that a fox asked the deity of Fushimi Inari to help people as its servant. The fox is not worshiped as the deity itself but is considered a divine messenger. Traditionally, these foxes are believed to be invisible, white foxes rather than the foxes we see in nature.

(3) From the Kamakura to the Edo Periods

During the Kamakura period, Shinto and Buddhism were blended at many temples and shrines. Each of the five main deities of Fushimi Inari was associated with a Buddhist counterpart, a practice that continued until the Meiji period when Shinto and Buddhism were separated. This fusion might be why some people wonder whether Fushimi Inari is a shrine or a temple.

Most Inari sites across Japan are shrines, and Fushimi Inari is considered the main one. However, some exceptions exist. For example, Toyokawa Inari in Aichi Prefecture is a Soto Zen Buddhist temple, and Saijo Inari in Okayama Prefecture is a Nichiren Buddhist temple. This diversity in worship styles can explain the occasional confusion over whether Inari sites are shrines or temples.

In the Muromachi period, the Onin War brought conflict to Fushimi Inari, as the Hosokawa clan, fighting the Yamana clan, used it as a base. The defeat of the Hosokawa clan resulted in the destruction of the entire mountain area of Fushimi Inari by fire. Originally, the main shrine was located on the mountain itself, but after the fire, it was rebuilt at the mountain’s base. Restoration took time, but around 100 years later, Toyotomi Hideyoshi donated the current main gate (Romon) in gratitude for his mother’s recovery from illness.

By the Edo period, the samurai class increasingly followed Buddhism, but the common people continued to visit Fushimi Inari, praying for abundant harvests and business success. Many people offered red torii gates in gratitude for answered prayers, giving rise to the famous Senbon Torii (thousands of torii gates) we see today. Around Japan, people began establishing Inari shrines upon discovering fox dens and honoring the deity with the highest rank title, Shoichi-i.

(4) From the Meiji Period to Today

During the turbulent times at the end of the Edo period, Fushimi Inari remained unharmed and entered the Meiji era peacefully. However, due to the government-enforced separation of Shinto and Buddhism, Buddhist statues and other items were removed, reestablishing Fushimi Inari as a Shinto shrine. An exception is the annual event known as Toji Gokuyo, where a portable shrine makes a stop at Toji Temple to receive Buddhist prayers, preserving the longstanding connection between the two sites.

In the Meiji era, changes in religious laws led to the shrine being officially named “Kanpei Taisha Inari Shrine.” After World War II, in 1946, it became a religious corporation, dropping the title “Kanpei Taisha” to avoid confusion with other Inari shrines, resulting in the name it is known by today, “Fushimi Inari Taisha.”

Highlights of Fushimi Inari

Let’s dive into some fascinating stories and legends surrounding Fushimi Inari.

While people often talk about the “Seven Mysteries of Fushimi Inari,” here, we’ll explore ten intriguing tales. These mysteries and legends add depth to the experience, so keeping them in mind can make your visit even more enriching and memorable.

1. Why So Many Torii Gates?

First up is the “Senbon Torii,” or “Thousand Torii Gates,” which may be the most iconic feature of Fushimi Inari. This mesmerizing path of vermilion gates is visually striking and attracts many visitors, especially those seeking a taste of Japan’s unique spiritual atmosphere. It even gained popularity through the American movie Memoirs of a Geisha, where a scene features the heroine running through these gates.

So, where exactly is the Senbon Torii? It begins right behind the main hall and forms a two-row entrance, as you can see in the image below. Passing through the Senbon Torii path will take you to the Okunoin, or inner sanctuary.

The biggest mystery behind the Senbon Torii is why there are so many gates in the first place. While it’s called “thousand gates,” Fushimi Inari actually has around 10,000 torii in total. The precise count along the main Senbon Torii pathway is unknown, but some say it’s slightly less than a thousand.

Historically, Inari shrines, dedicated to the gods of agriculture and prosperity, became widely popular among townspeople during the Edo period. People began dedicating torii gates as offerings when their prayers for success and fortune were answered. This practice led to the gradual accumulation of gates, especially as word of Fushimi Inari’s blessings spread.

Each additional torii reflects the gratitude of people whose wishes came true. It also represents the hope that wishes can “pass through” to fulfillment. The vermilion color of the gates is believed to repel evil and symbolize abundance. Traditionally, the paint also served as a protective coating, using cinnabar, which contains mercury to help preserve the wood.

To this day, anyone can dedicate a torii to the shrine; details are available on the shrine’s website. Depending on the gate’s size and location, the offering cost starts at around ¥175,000 for a smaller gate and can exceed ¥1,000,000 for larger ones.

2. What Is the “Shirushi no Sugi” (Significant Cedar)?

Every February, Fushimi Inari Taisha holds the Hatsumode Festival to honor its founding. During this time, visitors receive a “Shirushi no Sugi” branch, like the one in the picture, to bring home as a charm for family safety and business prosperity.

The sacred trees of Fushimi Inari are cedars, but instead of one specific cedar tree, it refers to all the cedars on Mount Inari. The belief in the cedar’s power to ward off evil dates back to ancient times. During the Heian period, nobles making pilgrimage to Kumano Shrine would first stop at Fushimi Inari, collect a cedar branch for protection, and carry it with them. They’d return to Fushimi Inari on the way back, offering thanks and taking another branch as a safe return token.

Back then, safety was a serious concern, especially when traveling, so the protective power of Fushimi Inari’s cedar was highly valued. This tradition continues today with the “Shirushi no Sugi.”

3. What is Oyashima Shrine?

About 200-300 meters north of the main shrine, on the path to Osanba Inari, lies Yashima Pond. Beside it, you’ll find Oyashima Shrine, a small, tucked-away spot that few visitors notice and could easily pass by. Unlike typical shrines, Oyashima Shrine has no shrine building. Instead, it’s a small, sacred area enclosed by a red fence and is off-limits for entry.

Oyashima Shrine is considered a subordinate shrine of Fushimi Inari, dedicated to Oyashima no Okami, a deity that represents the entirety of ancient Japan. This shrine’s simplicity contrasts with the grand scale of its deity, adding a unique sense of mystery to the visit.

4. What is the Omokaru Stone?

The “Omokaru Stone” is located in the inner sanctuary, behind the thousand torii gates (Senbon Torii) at Okunoin Shrine. Look carefully—it’s slightly set back from the main path. Here, you’ll find two stone lanterns with stone tops known as the Omokaru Stones.

To try the Omokaru Stone ritual, make a wish, then lift one of the stone tops. If it feels light, it’s believed your wish will come true; if it feels heavy, your wish may remain unfulfilled. It’s a fun and symbolic way to test your wishes.

The origin of the Omokaru Stone is unknown, but similar stones can be found at other shrines, like Imamiya Shrine in Kyoto and Shitennoji Temple in Osaka. Feel free to try this ancient stone “divination” on your visit!

5. What’s in Shinike Pond?

About 300 meters northeast of the Inner Shrine lies Shinike Pond (also called Kodama-ga-Ike). Since the area is a bit off the main path, many visitors turn back at the Inner Shrine, making Shinike a peaceful, quiet spot. There’s a unique legend associated with this pond: if you’re searching for someone who is missing, you can clap your hands by the pond. It’s said that the echo will point you in the direction of the person.

Near the pond’s edge, you’ll find a small shrine dedicated to the deity Kumataka Okami.

6. What is Osanba Inari?

Continuing past Oyashima Shrine and Yashima Pond, you’ll come across a shrine with an unusual name: Osanba Inari, also known as the “Midwife Inari.” Located at the base of Mount Inari, Osanba Inari is dedicated to safe childbirth.

It’s believed that since foxes, Inari’s sacred animals, are known for their fertility, this shrine brings blessings for a smooth delivery. Tradition says if you take one of the shrine’s candle remnants home and let it burn, the time it takes to burn out will indicate the ease of the childbirth.

7. What is the Nune Torii?

When climbing Mount Inari, if you take the right path from Yotsutsuji intersection, you’ll come across a small shrine called Kadasha on the slope of Ma-no-Mine. Here stands a unique torii gate known as the “Nune Torii.” Normally, at Fushimi Inari, the torii gates feature a central support post beneath the top crossbars, but the Nune Torii has an unusual umbrella-like or “figure-eight” shape, which is rarely seen. The only other example in Kyoto is at Nishiki Tenmangu Shrine on Shin-Kyogoku Street.

Kadasha enshrines the Kadano family, former priests of Fushimi Inari. Their ancestor is said to be Ryutota, the mountain deity of Mount Inari, and they were also historically connected to the monk Kukai. The family produced prominent scholars, including Kada no Azumamaro, a famous Edo-period scholar of Japanese classics.

8. What is the Tsurugi Stone?

On the north side of the summit Ichinomine, you’ll find Mitsurugisha Shrine, which houses the mysterious “Tsurugi Stone” behind it. This stone, called the “Thunder Stone,” is said to seal in lightning.

Mitsurugisha, also known as Choja Shrine, has long been a sacred place for worship and is considered a powerful spiritual spot at Fushimi Inari. Nearby, you’ll also find a spring called “Yakiba no Mizu.” According to legend, the famous swordsmith Sanjo Munechika, with help from the deity Inari, used water from this spring to forge the legendary sword “Kogitsunemaru.”

9. Why Are There So Many Inari Mounds?

Fushimi Inari Shrine is dotted with countless small “Inari mounds,” which are miniature stone markers often inscribed with names. Worshippers place these mounds all over Mount Inari to show their devotion, with numbers estimated to reach tens of thousands. This abundance highlights the deep faith people have held here over time. You can spot these mounds all along the pathways, particularly around sacred spots called the “Seven Miracles,” such as Ichinomine, Ninomiya, Sannomiya, and Mitsurugisha Shrine.

10. Why Is Inari Mountain’s Soil Special?

There is a traditional belief that taking soil from Mount Inari and spreading it on one’s own fields would bring a bountiful harvest. Although Fushimi Inari is now often associated with business prosperity, its original purpose was to bring good fortune in rice cultivation and abundant harvests, making this custom understandable. Today, instead of taking soil, many people bring back “Fushimi dolls,” small figurines made from Fushimi clay, as symbols of good fortune.

Fushimi Inari Taisha – Basic Information

Address: 68 Fukakusa Yabunouchi-cho, Fushimi-ku, Kyoto

Map: Google Maps

Phone Number: (075) 641-7331

Closed Days: Open year-round for general visits

Opening Hours: Open 24 hours for general visits

Entrance fee: Free

We’ve introduced many fascinating aspects of Fushimi Inari Taisha so far. Beyond its well-known reputation as a place where people pray for business success, Fushimi Inari offers much more: an expansive grounds filled with various shrines, stone mounds, and a deep-rooted history, along with intriguing stories and legends.

The famous red Torii path, the “Senbon Torii,” creates an unforgettable sight, making Fushimi Inari a popular destination, especially among international visitors. We hope this article helps you experience Fushimi Inari in a richer, more in-depth way.

▼ Related Articles for Kyoto Sightseeing